KNOWLEDGE AND THE KNOWER—

WHAT COUNTS AS KNOWLEDGE?

GOOD AND BAD EXPLANATIONS

Can a well chosen metaphor be a good explanation?

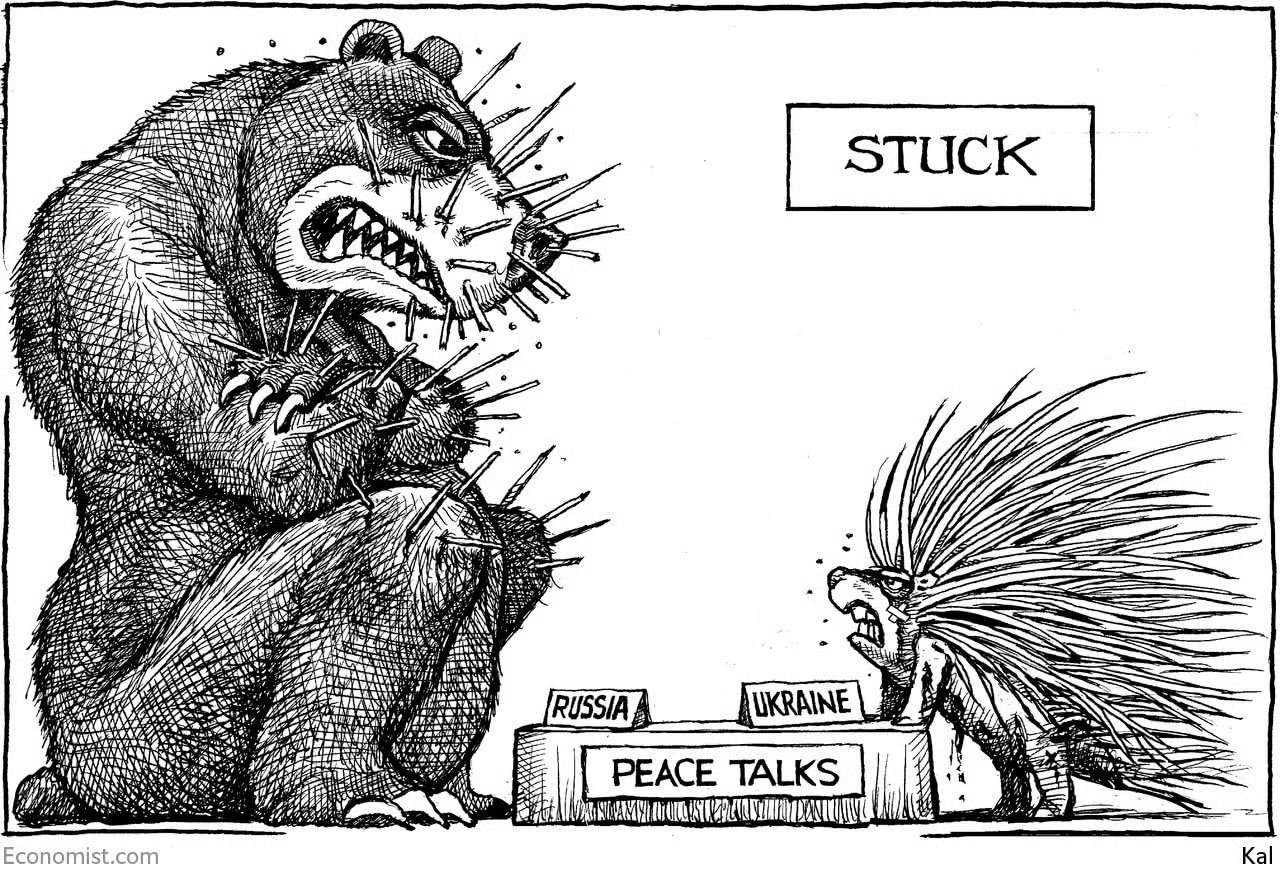

Source: KAL’s cartoon in the Economist—March 31, 2022. Visit Kaltoons official site.

Explanation as problem solving

Explanations reveal, unravel, demystify and elucidate problems that engage our attention. Our explanations arise from epistemic hunger—the need to question, know, and understand. Our knowledge quest begins with questions like:

What’s going on here?

How does it work?

Why is it happening?

What does it mean?

What is it like?

Is it significant?

How does it connect?

What on earth is going on here?

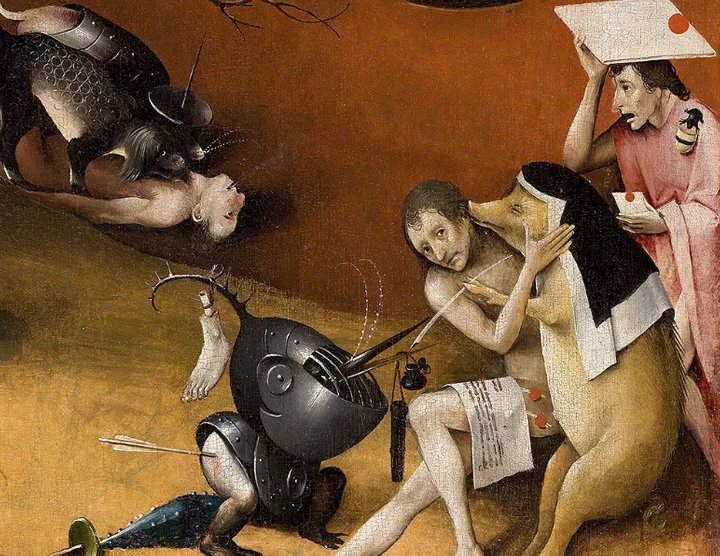

Detail from Hieronymus Bosch (1490-1510) The Garden of Earthly Delights. Oil on oak panels. Museo del Prado, Madrid

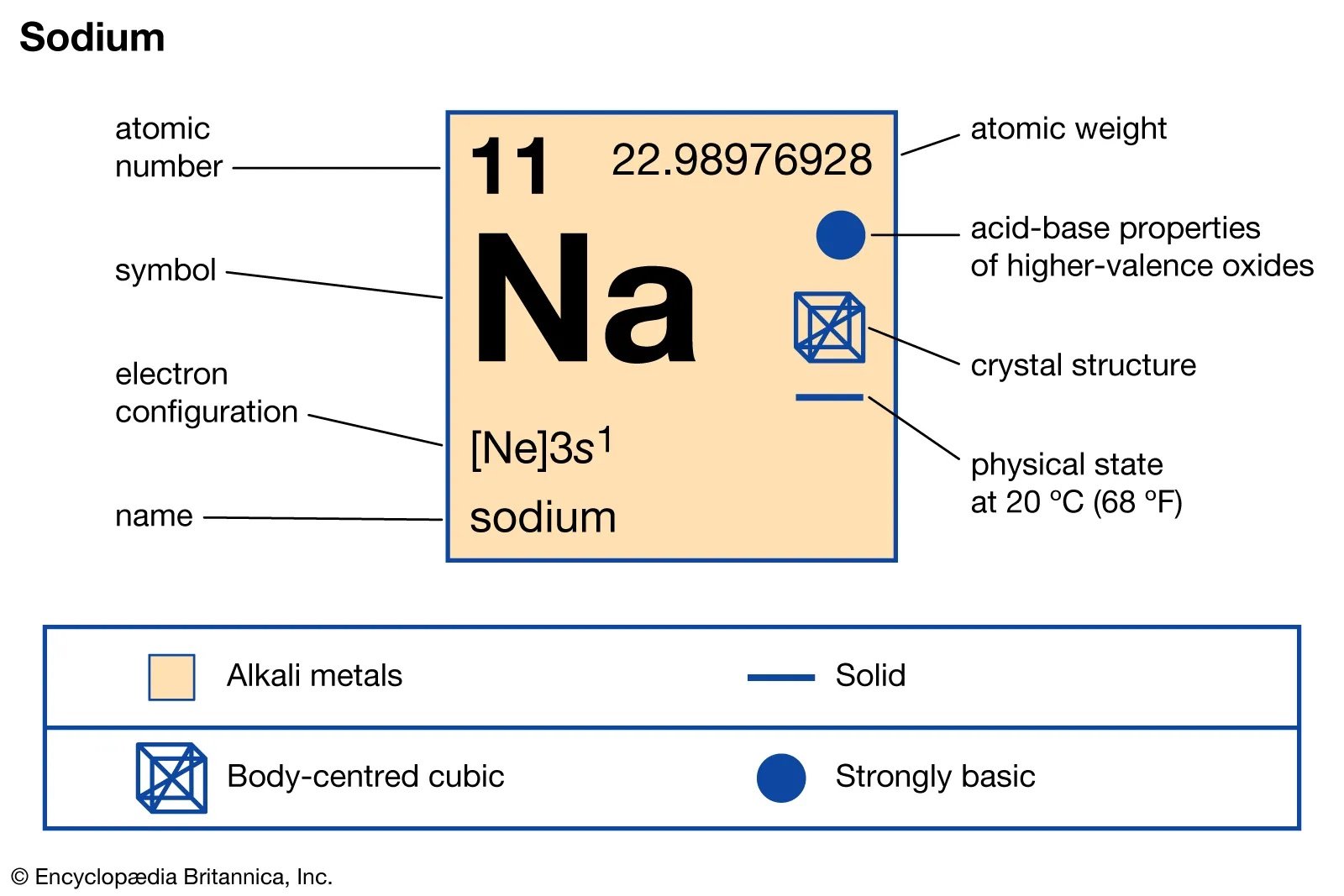

The products of human ingenuity span an enormous range. It is almost impossible to know what Hieronymous Bosch was attempting to explain in his enigmatic masterpiece five hundred years after it was created. Contrast this with the Sodium (Na) graphic below. Sodium is just one of the hundred or so chemical elements mapped in the periodic table. As a standalone, this block depicting Na atom characteristics, has remarkable explanatory power for beginning chemistry students.

REaCh AND VARIABILITY

Explanations come with a set of assumptions and are theory-laden. They often have reach and implications that go way beyond their original conception. Good explanations are apt and hard to vary. They are especially powerful when supported by specific, real-world instances.

In the class activities that follow students explore how scientists, mathematicians and artists formulate explanations in their respective Area of Knowledge domains. The activities lean heavily on the work of Karl Popper and especially David Deutsch’s thought provoking 2011 book, The Beginnings of Infinity: Explanations that Transform the World. Penguin, New York.

Class activity i—the gods did it!

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1621–22) The Rape of Persephone. Carrara marble sculpture. Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Begin the class by sharing and soliciting student reaction to the Ukraine impasse cartoon, the detail from Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, and the sodium graphic from the periodic table.

Continue with a silent reading of David Deutsch’s explanation for the coming of the seasons according to Ancient Greek mythology. Next solicit student volunteers to read aloud the four paragraphs (include the citation).

“Long ago, Hades, god of the underworld, kidnapped and raped Persephone, goddess of the spring. Then Persephone’s mother, Demeter, goddess of the Earth and agriculture, negotiated a contract for her daughter’s release, which specified that Persephone would marry Hades and eat a magic seed that would compel her to visit him once a year thereafter. Whenever Persephone was away fulfilling this obligation, Demeter became sad and would command the world to become cold and bleak so that nothing could grow...

…if the cause of winter is the Demeter’s periodic sadness, then winter must happen everywhere on earth at the same time. Therefore, if the ancient Greeks had known that a warm growing season occurs in Australia at the very moment when, as they believed, Demeter is at her saddest, they could have inferred that there was something wrong with the explanation of seasons…

In Nordic mythology, seasons are caused by the changing fortunes of Freyr, the god of spring, in his eternal war with the forces of cold and darkness. Whenever Freyr is winning, the Earth is warm; when he is losing, it is cold.

…we are left with the same core explanation in both cases: the gods did it.

”

Without revealing the animated graphic below (showing the earth tilted 23 degrees on its axis orbiting the sun), kick off a full-class, preliminary discussion using these generative questions:

1. What is good and what is bad about this prescientific explanation?

2. The myth is at least two and a half thousand years old. How useful or reliable do you think the explanation would have been back then?

3. What assumptions are contained in this explanation?

4. Does the explanation have reach—wider applications and connections?

5. Is the explanation hard to vary? Can we change some of the characters or details in this explanation without it making a difference to its predicted outcomes?

6. How emotionally satisfying is the explanation? Provide reasons.

7. Why has this ancient myth persisted?

It’s all about the earth’s tilt

As students respond to the generative questions, it is very likely that the standard scientific causal explanation for the seasons will emerge. When this happens share the animated graphic below for clarity. Later, to maximize understanding, invite the class to visit briefly Nasa’s What causes the seasons?

Follow up by asking students to apply generative questions 3 through 6 systematically to the accepted scientific explanation for the seasons.

Finally, share this whimsical scene from Disney’s 1994 The Lion King movie. Given the TOK discussion so far, anticipate a cascade of student comments about the uncanny explanatory power of Pumbaa the warthog’s transcendent connection to distant stars.

CLASS ACTIVITY II—Written ASSIGNMENT:

Why doesn’t the stomach digest itself?

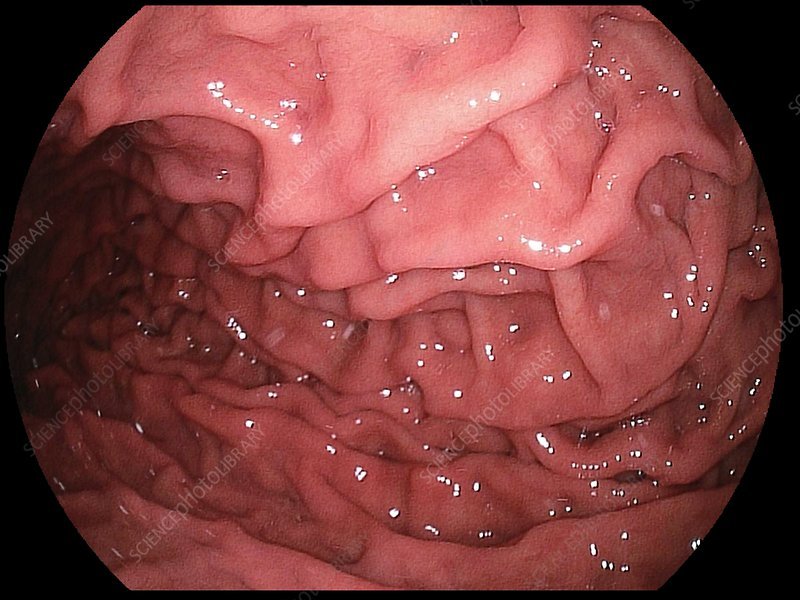

Human stomach lining viewed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Written assignment—400 words

The stomach produces Pepsin, an enzyme that digests protein. A potential problem arises. The stomach is a muscular organ that is mostly made of protein! Why doesn’t the stomach digest itself?

(a) Research this problem online. Provide a convincing written explanation for why the stomach does not digest itself?

(b) Justify whether or not your explanation is a good explanation.

CLASS ACTIVITY III—COINCIDENCE? I think not!

Young children are taught the elegant and surprising fingers trick for the 9 times table. We can quickly demonstrate that it works for all 10 fingers. Our intuition tells us this cannot be a coincidence; and demonstration is not explanation.

Provide scratch paper for brainstorming and diagramming. Have students work in pairs. Challenge them to find a lucid mathematical explanation for the multiples of 9 finger trick. Successful pairs will report back their findings to the class using the whiteboard. The following guiding questions could be helpful for generating audience feedback and critique.

Is this a convincing explanation? Why? Why not?

Perhaps with some refinement, does this explanation have the status of mathematical proof?

CLASS ACTIVITY IV—

DO GOOD EXPLANATIONS HAVE TO BE TRUE?

This class activity has a family resemblance to the TOK Exhibition. It consists of a portfolio of curated exhibits and a triad of slippery knowledge questions. Students should examine the entire portfolio before engaging with the questions.

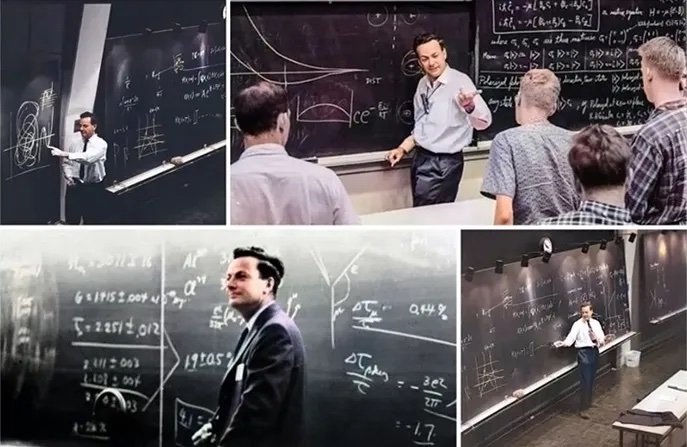

Exhibit #1 includes imagery of Richard Feynman in action and his famous “key to science” quote. A live video link is included.

Exhibit #2 is a TEDEd video about Nobel Prize winning work on what causes stomach ulcers. In 1984 Barry Marshall silenced fierce resistance from the established scientific community by deliberately infecting himself with Heliobactor pylori bacteria.

Exhibit #3 is a quote from Orwell’s Animal Farm. Noam Chomsky’s assertion that we can learn more from literature than neuroscience is also included. Students should also be encouraged to think of specific examples from their own IB literature studies and personal reading to add a more sophisticated dimension to the paradoxical and usually unexamined notion that “fiction” may lead us to truth.

EXHIBIT #1: Richard Feynman ON scienCe

"It doesn't matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn't matter how smart you are. If it disagrees with experiment, it's wrong." - Richard Feynman

EXHIBIT #2: helicobacter pylori

Heliobactor pylori

EXHIBIT #3: LITERARY ENCOUNTER

“It is quite possible—overwhelmingly probable, one might guess—that we will always learn more about human life and human personality from novels than from scientific psychology. ”

FROM ORWELL’S Animal farm

“It had become usual to give Napoleon the Credit for every Successful achievement and every stroke of good fortune. You would often hear one hen remark to another, “Under the guidance of our leader, Comrade Napoleon, I have laid five eggs in six days” or two cows, enjoying a drink at the pool, would exclaim,

“thanks to the leadership of Comrade Napoleon, how excellent this water tastes!”

”

PORTFOLIO KNOWLEDGE QUESTIONS

Place students in random groups of four, each with an assigned Facilitator, Disruptor, Scribe and Presenter. Allow a timed 12 minutes for in-depth conversation to be followed by presentations and class discussion.

When mathematicians, scientists, historians or novelists claim that they have explained something, are they using the word 'explain' in the same way?

Are some things unknowable?

Which is more important: what can be explained or what cannot be explained?

““Are you lost, Daddy?” I asked tenderly. “Shut up,” he explained.”

”