OPTIONAL THEME:

KNOWLEDGE AND LANGUAGE

LOGICAL FALLACIES

Francisco Goya (1791-92) El pelele (The Straw Manikin) Oil on canvas Museo del Prado, Madrid

After the first video ask the whole class if they have studied or come across logical fallacies before. Ask them where they think the formal Latin names came from and whether or not it is important to memorize them?

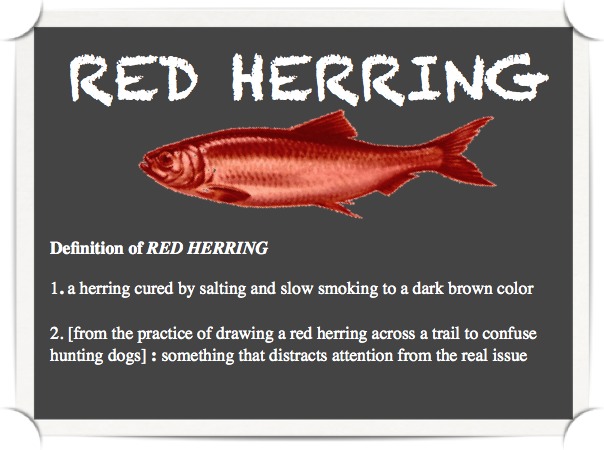

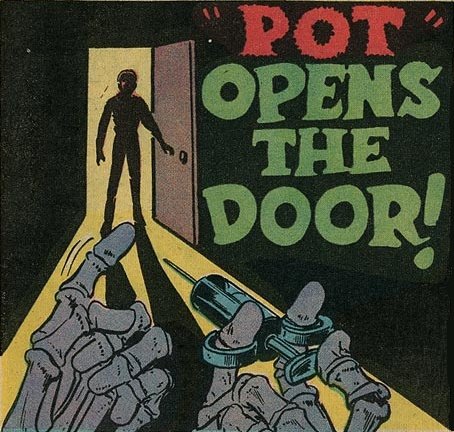

After the second video, to stimulate lively conversation, ask them “What is a red herring?” “What about a slippery slope?” “Has anybody heard of the straw man argument evoked above in the Goya painting?"

CLASS ACTIVITY I: RECOGNIZING the flawed logic

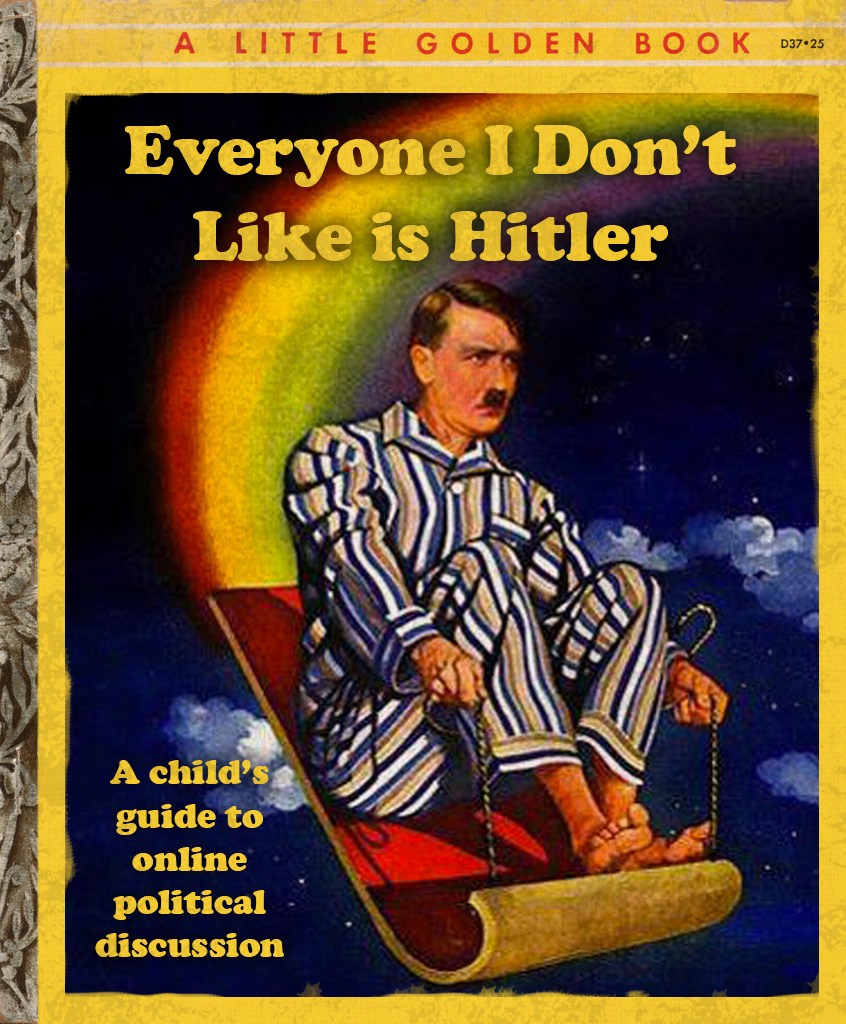

Ask students to decode these images and fully assimilate the meaning of the "Red herring," "Slippery slope" and "Straw man" fallacies. Challenge the students to write down a real life example from their own experience (in or out of school) in a single sentence for each.

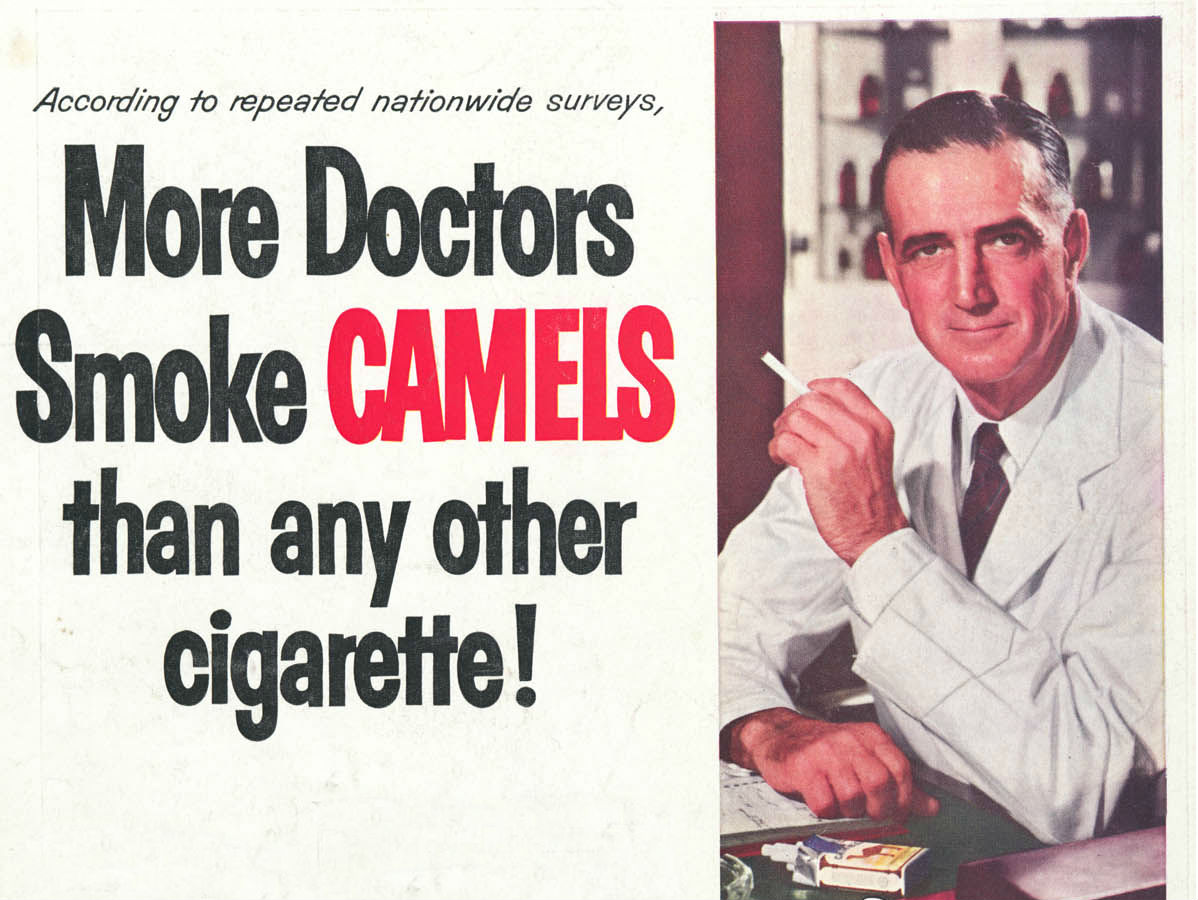

Below are four more important ones to tackle. Again, as contrived as it seems, students should make a point of doggedly contriving their own real life examples and writing them carefully in grammatical sentences. Knowing "official" names for the fallacies is not expected. They will be revealed in a moment. The important thing is to follow the pattern of the flawed logic.

The four fallacies are: ad hominem (attack the person not their arguments), false dichotomy, false analogy, and the smoking doctor combines consensum gentium (wisdom of the crowd) and a plea to authority.

The smoking doctor advertising campaign was not a joke at the time. Scientific evidence linking cigarette smoking to lung cancer and heart disease had been downplayed until the sixties. This was aided by the grim complication that much of the more convincing empirical evidence had been published by nazi scientists.

Ask students what they make of the following, much more recent, appeal to the authority of scientific consensus. See if students recall, and can make a connection with the "wisdom of the crowd vs. jury of geeks" viewpoint of Naomi Oreskes in Is there a scientific method?

Recalling another previous unit of inquiry, ask students to consider the claim that "History is what historians actually do." This was encountered in the introductory remarks of Coherence Correspondence and Pragmatic Theories of Truth. "History is what historians actually do" is a central idea in TOK when elaborated, but as a stand-alone sentence it has an inherent flaw. The evolutionary biology cliche "survival of the fittest" has similar issues. Ask students what they think.

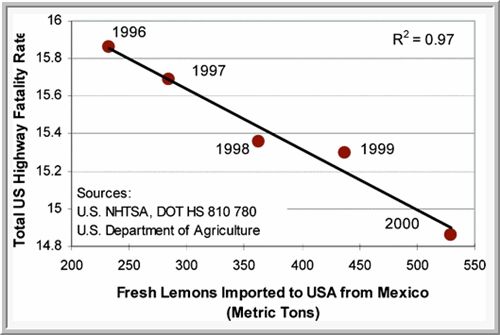

Continuing in scientific vein, extend the discussion by asking why confusing causation with correlation is hazardous in the various Areas of Knowledge. Insist on some concrete examples.

When the time is ripe, bring the conversation back on task by asking what the class thinks about the slacker student’s remark at the end of the first video, when he insists that he will not need to know about logical fallacies since he intends to major in political advertising.

CLASS ACTIVITY II:

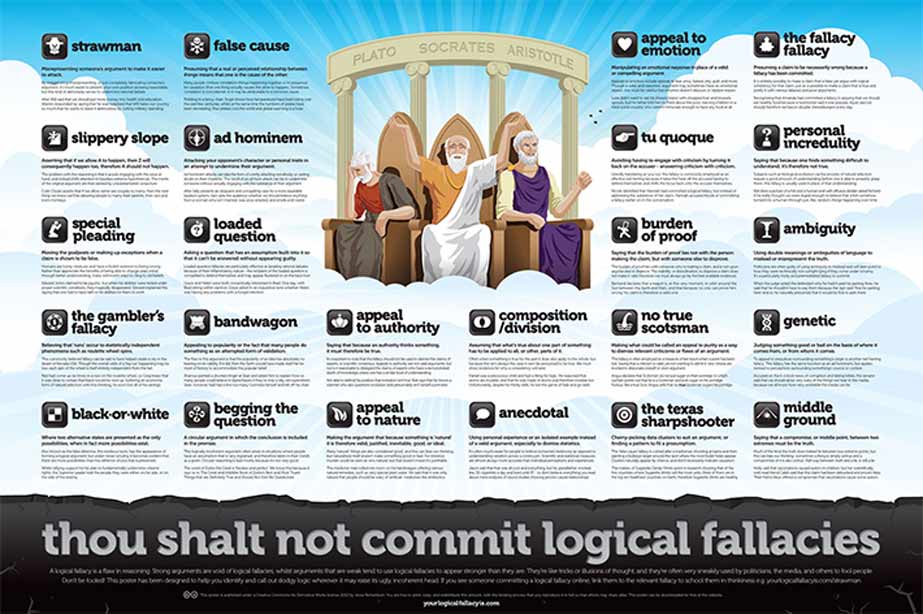

Thou shalt not commit logical fallacies

Next tell students to go online working solo. Visit the interactive Thou shalt not commit logical fallacies at the Your Logical Fallacies creative commons website.

Here is the superlative purchasable and downloadable poster from the Your Logical Fallacies creative commons website. Worthy of wall space in any TOK classroom.

Students should navigate over each of the live icons to reveal definitions and examples of the 24 fallacies offered. Students are told they should choose a favorite fallacy that was not mentioned in the first class activity, Their task is to memorize the name and definition of their fallacy and have an authentic real-life example of their own ready. Allow 5 minutes for this activity and create some tension by telling students in advance that eight of them will be chosen to champion their favorite logical fallacies without the aid of notes.

MONTY PYTHON WITCH SCENE

At the beginning of the next class, mostly for fun, the whole class views the famous Monty Python Witch scene which is chock full of hilariously surreal, fallacious, idiotic arguments.

All witches are things that can burn.

All things that can burn are made of wood.

Therefore, all witches are made of wood.

All things that are made of wood are things that can float.

All things that weigh as much as a duck are things that can float.

So all things that weigh as much as a duck are things that are made of wood.

Therefore, all witches are things that weigh as much as a duck.

This thing is a thing that weighs as much as a duck.

Therefore, this thing is a witch.