AREAS OF KNOWLEDGE:

HISTORY

HISTORY IS NOT WHAT HAPPENED

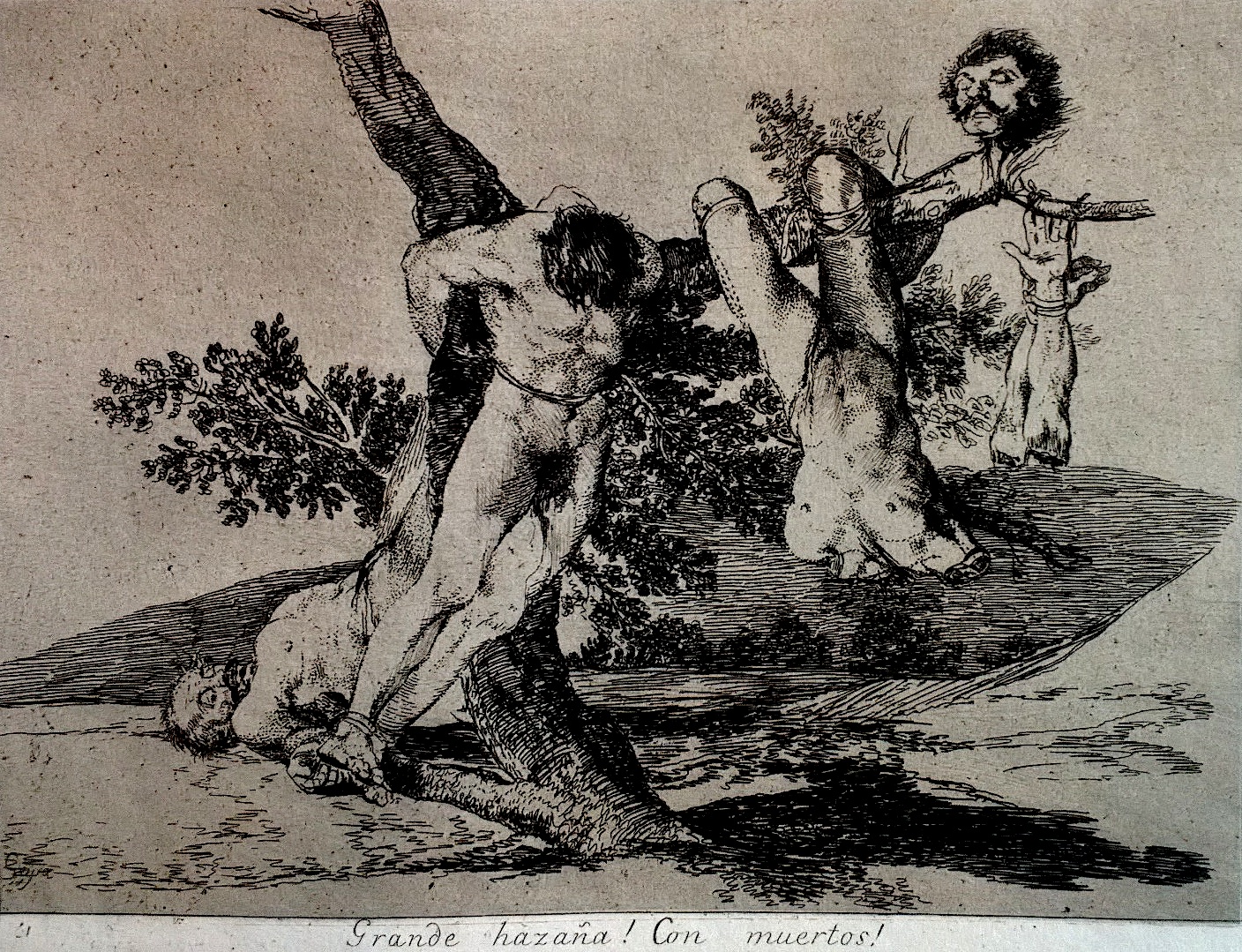

Francisco de Goya (1810-20) Plate 39 of Disasters of War: Grande hazaña! Con muertos! (A heroic feat! With dead men!) Etching and aquatint. Prado, Madrid

“History is important. If you don’t know history it is as if you were born yesterday. And if you were born yesterday, anybody up there in a position of power can tell you anything, and you have no way of checking up on it.

”

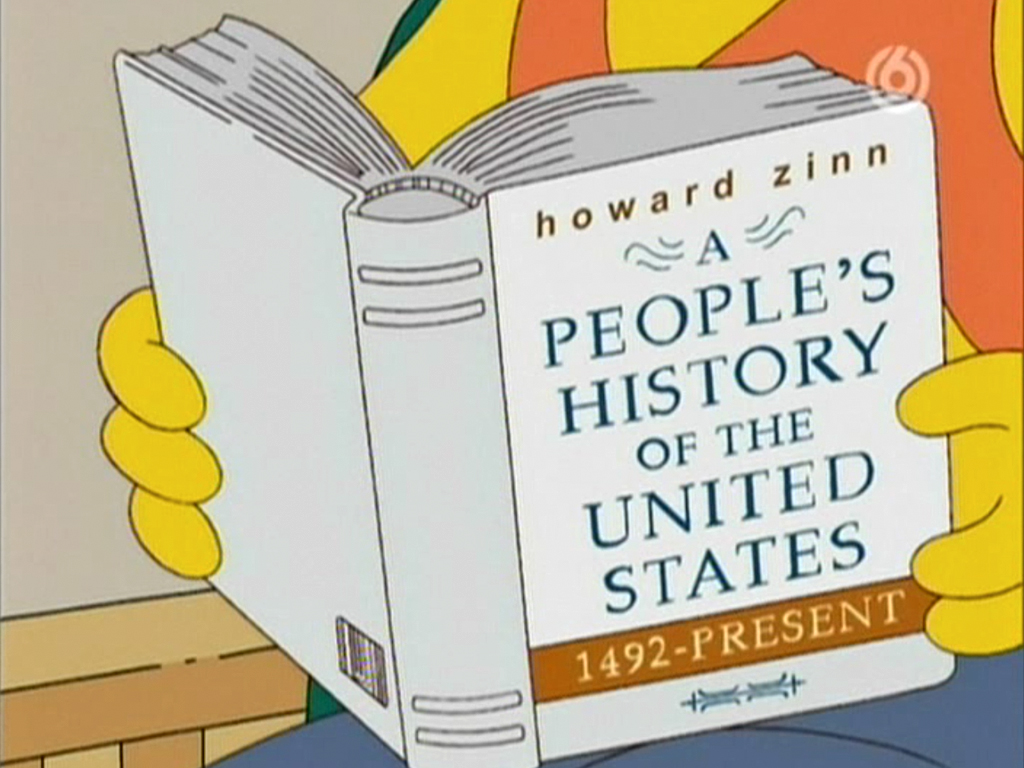

Who is reading Howard Zinn's iconoclastic book?

“Historians do not, as too many of my colleagues keep mindlessly repeating, “reconstruct” the past. What historians do is produce knowledge about the past, or, with respect to each individual, fallible historian, produce contributions to knowledge about the past. Thus the best and most concise definition of history is: “The bodies of knowledge about the past produced by historians, together with everything that is involved in the production, communication of, and teaching about that knowledge.””

CLASS ACTIVITY i: WHAT HISTORIANS DO

Begin by asking volunteer students to read the Howard Zinn and Arthur Marwick quotes. Mention to the class that Zinn is famous for a life of civil rights and anti-war activism; and his revisionist A People's History of the United States. Marwick was a respected Brit historian who introduced the notion of "witting vs. unwitting testimony." It is worth asking students to reflect for a moment on why Marwick made this distinction when weighing historical evidence.

Continue in similar vein with two new volunteers; reading alternative paragraphs of an official distillation of the nature of history from the International Baccalaureate Organization itself. Include the definitive “Ten Year Rule” from the history Extended Essay guidelines. Ask the class to reflect on how much this description has aligned with their actual experience in school history classes.

“As we cannot directly observe historical events, documentary evidence plays a vital role in helping historians to understand and interpret the past. This raises questions about the reliability of that evidence, particularly given that historical sources are often incomplete and that different sources can corroborate, complement or contradict each other.

In addition to being heavily evidence-based, history is also an interpretive discipline that allows for multiple perspectives and opinions. Students could be encouraged to consider the role and importance of historians, particularly in terms of why their interpretations may differ or how we evaluate conflicting interpretations of past events.

Students could also consider why some might claim that there is always a subjective element in historical writing because historians are influenced by the historical and social environment in which they are writing—which unavoidably affects their selection and interpretation of evidence.

An interesting focus for discussions could be the concept of historical significance. For example, students could consider why particular aspects of history have been recorded and preserved whereas others have been lost or excluded from historical accounts.

They could also consider the way that history is sometimes used to promote a particular dominant perspective or consider how specific groups, such as minorities or women, may have experienced events in the past differently.

”

Thousands of Benin Bronzes in were looted by British colonial troops in 1897. The British Museum received a formal request for the return of ‘Nigerian antiquities’ in 2021.

Photo credit:© Mike Peel

“Essays that focus on events of the past 10 years are not acceptable, as these are regarded as current affairs, not history.”

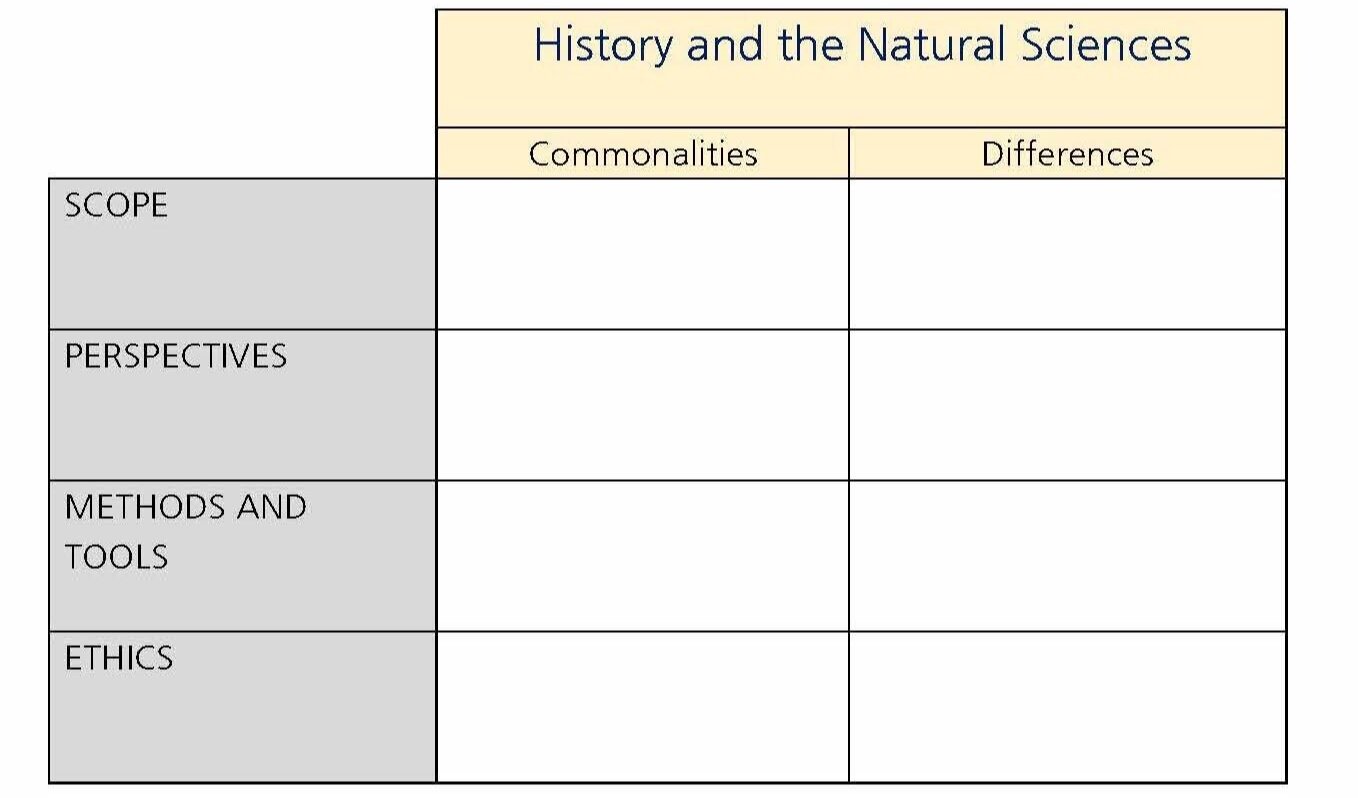

CLASS ACTIVITY II: COMPARING HISTORY TO SCIENCE

Place students in groups of three. Allow a strictly timed six minutes to freely brainstorm a comparison of history and science. Tell students to write down bullet points under two simple headings: "differences" and "similarities."

Next combine trios to make groups of six. Tell them to nominate a facilitator and scribe. Next allow a timed four minutes to distill a single master list. They could add a third heading: "probably wrong or very controversial" to capture any wild ideas for later discussion.

Finally provide groups with several copies of the following table (so that they can produce several drafts and a final clean copy.) The task is to take their similarity and differences bullet points and arrange them according to the TOK Framework. Lively debate should ensue. The teacher should circulate between the groups to provide clarity on the four elements of the framework. Print or upload pdf.

When the task has exhausted itself, ask that all six participants sign the final clean copy. Collect them. Before the next class meeting the teacher should produce a distillation of the efforts of the entire class for review and some whole class meta-discussion about the two Areas of Knowledge and the effectiveness of the methodology of how we as a class got there.

If all goes well there should be ample evidence of the power of collective thinking--including the value of allowing some opportunity for free brainstorming, followed by a systematic reining in.

After the to-and-fro of collective discussion and gentle teacher intervention it should be clear that history is not what happened. What happened has gone. History is the story telling that historians do. The historian selects from the vestigial traces of evidence in order to weave a coherent plot. This involves making judgment calls about what is significant and meaningful and what is not.

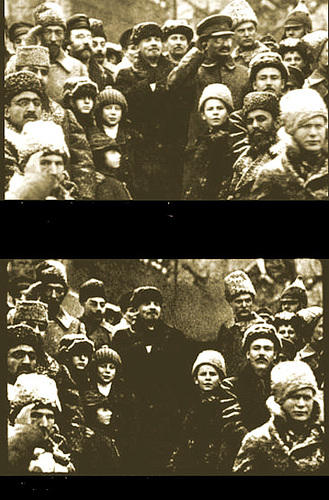

CODA: TROTSKY AIR-BRUSHED

FOR CLASS DISCUSSION

To what extent are photographs reliable historical sources? What is it about historic photographs that make them categorically different from oil paintings?

Would images like these be successful propaganda today?

What recent technological advances have further debased the notion that “the camera cannot lie”?

How should we approach academic history written under the auspices a totalitarian regime?

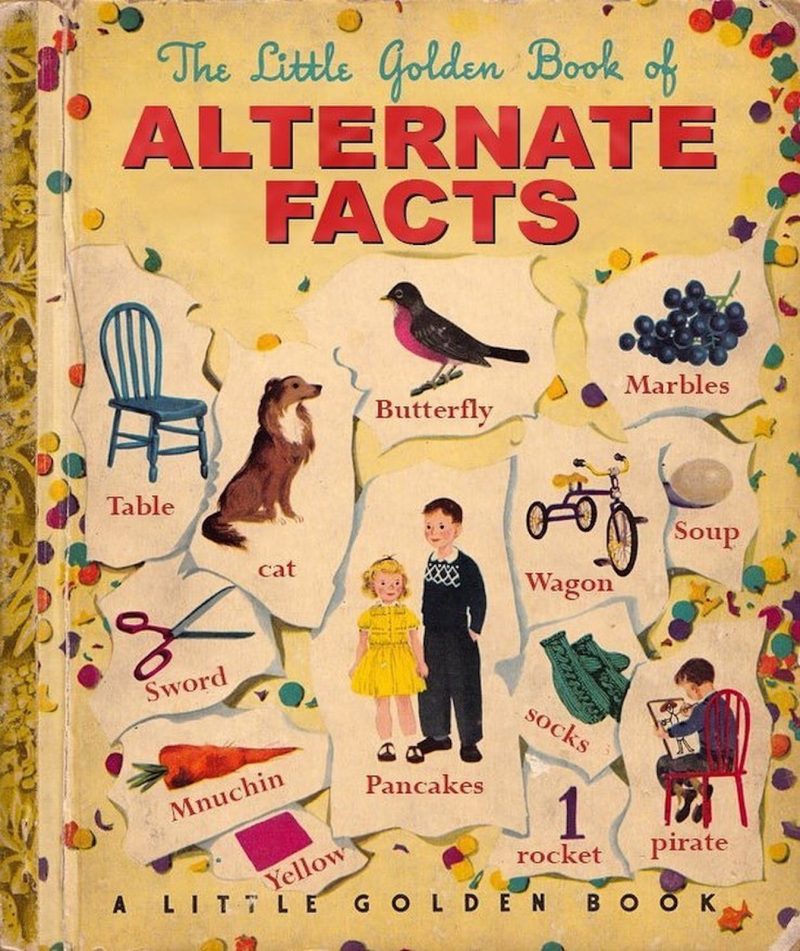

This timely collage work by illustrator Tim O'Brien evokes Magritte and Orwell.