KNOWLEDGE AND THE KNOWER—

WHAT COUNTS AS KNOWLEDGE?

INSTANTIATION—WHERE IS KNOWLEDGE?

Smart ape juxtaposed with voluminous sets of digital data

Image source: Schmidt Futures AI postdoctoral fellowship program at Oxford University.

RAW DATA AND INFORMATION

Data, information and knowledge can be understood as a strict hierarchy of increasing complexity; or as labels used informally and more or less interchangeably in everyday conversation. As a commonsense entry point, let’s agree for now that:

Information is organized raw data

KNOWLEDGE—SOMETHING TRUE AND USEFUL?

Knowledge itself is a tad more elusive and slippery to define. Lest we forget that entire epistemologically-flavored academic courses (TOK included) have been developed to explore what knowing is.

TOK students were introduced to traditional approaches to knowledge in the Student knowledge claims activity. They explored the difference between knowledge by description and knowledge by acquaintance in the Knowing that and knowing how written assignment. They also grappled with the strengths, and some of the inherent limitations, of the notion of Justified True Belief.

In short—even at this very early stage of the TOK course—students will have developed a sense of what knowledge is and how knowledge is acquired. They recognize the value of relentlessly asking “How do we know that?”

Knowledge is hard to define but we know it when we see it. Rather than wordsmithing the concept of knowledge to oblivion; we will adopt a “Look, don't overthink!” approach.

The class activities that follow provide an unsettling, messy-real-world, close encounter with a fundamental question:

What counts as knowledge and where is it located?

A quasi-safe, commonsense starting point is to adopt the position that knowledge cannot exist without a conscious, sentient knower. Things start to get more interesting when we consider the status of “information/knowledge” instantiated in non-sentient physical objects and organisms at various scales, as well as the myriad artifacts of technology and culture—including language itself.

CLASS ACTIVITY I:

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A BLINK AND A WINK

Begin by projecting this collage of three images to the whole class. Jump straight in by asking:

What data does the thermometer display and how does it work?

What does thermostat do?

Compare and contrast these two products of human technology with melting ice?

It may or may not be necessary to ask

Does the ice know that it is melting? Does the mercury in the thermometer know it is rising? Does the thermostat know when to turn the heating on or off?

Next project this simplified model for homeostatic temperature control in humans and the photo of the Central Arctic Inuit family in their temporary snow house.

Continue the class conversation with:

“As far as the knowledge is concerned, how do these two human scenarios compare to the thermostat?”

Finally consolidate the activity by having a student read the following whimsical poem:

“Ice —

Melts.

Mercury rises.

Thermostat switches.

Body —

Shivers or sweats.

Take off that warm coat.

Place another log on the fire.

There’s a mighty difference —

Between a blink

And a wink!

”

Thank the student reader and without further comment ask the class:

So… what is the difference between a blink and a wink?

CLASS ACTIVITY II:

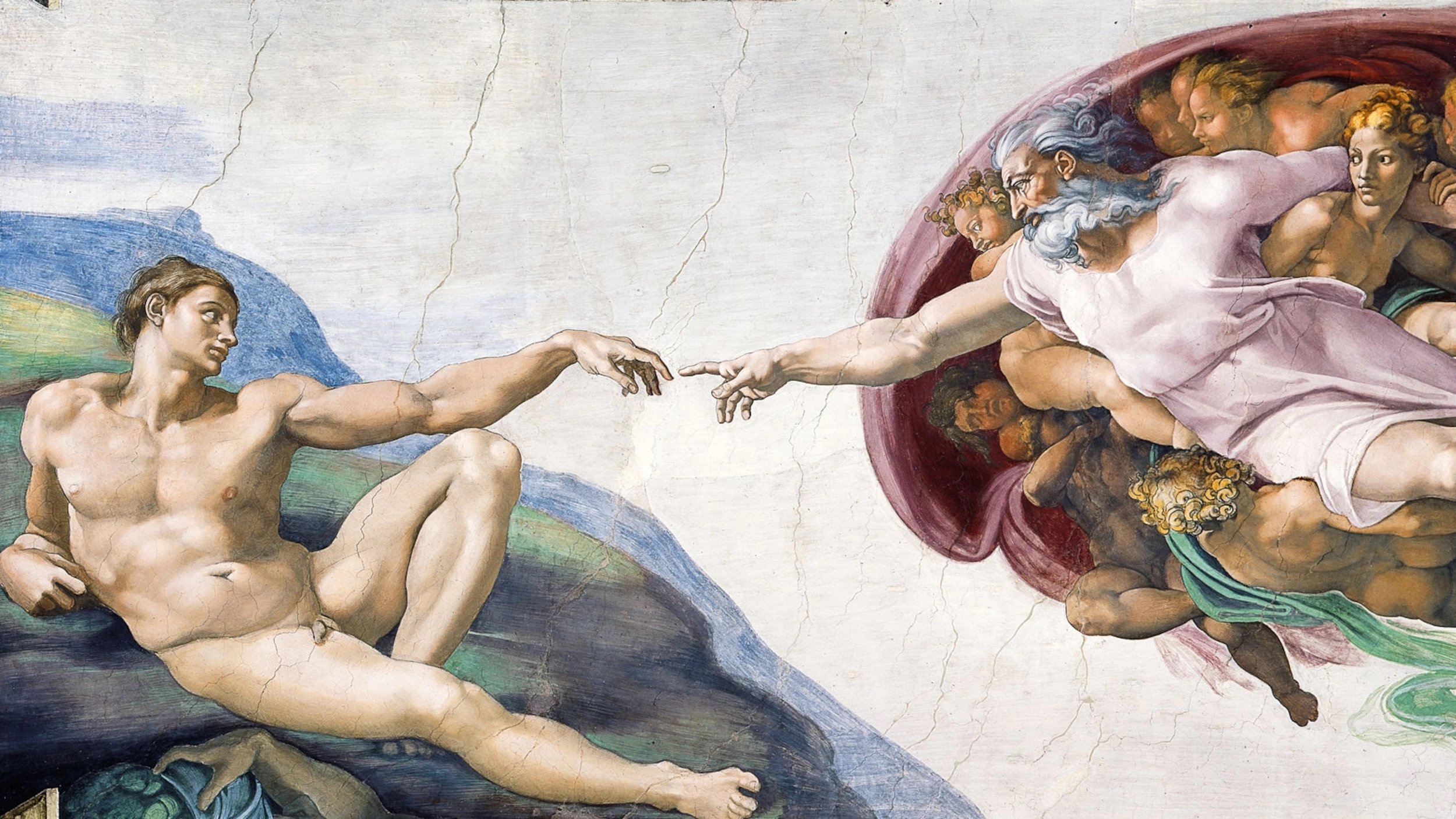

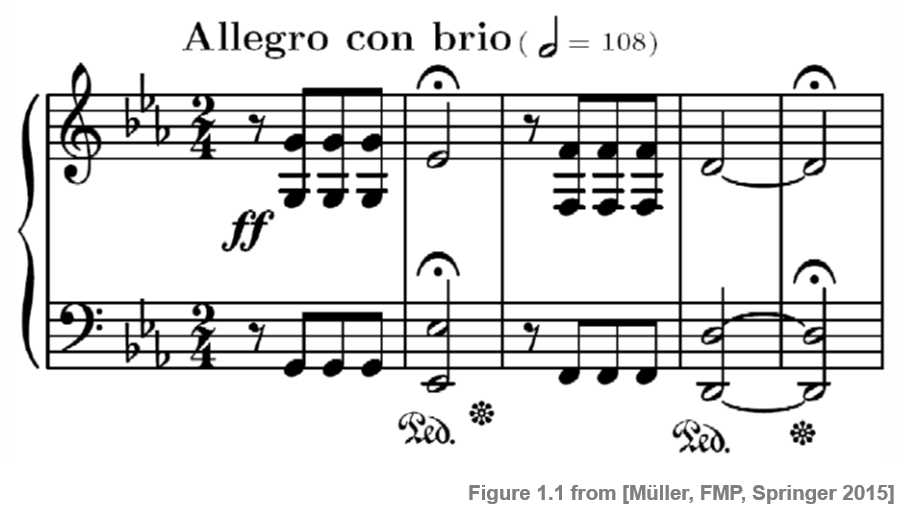

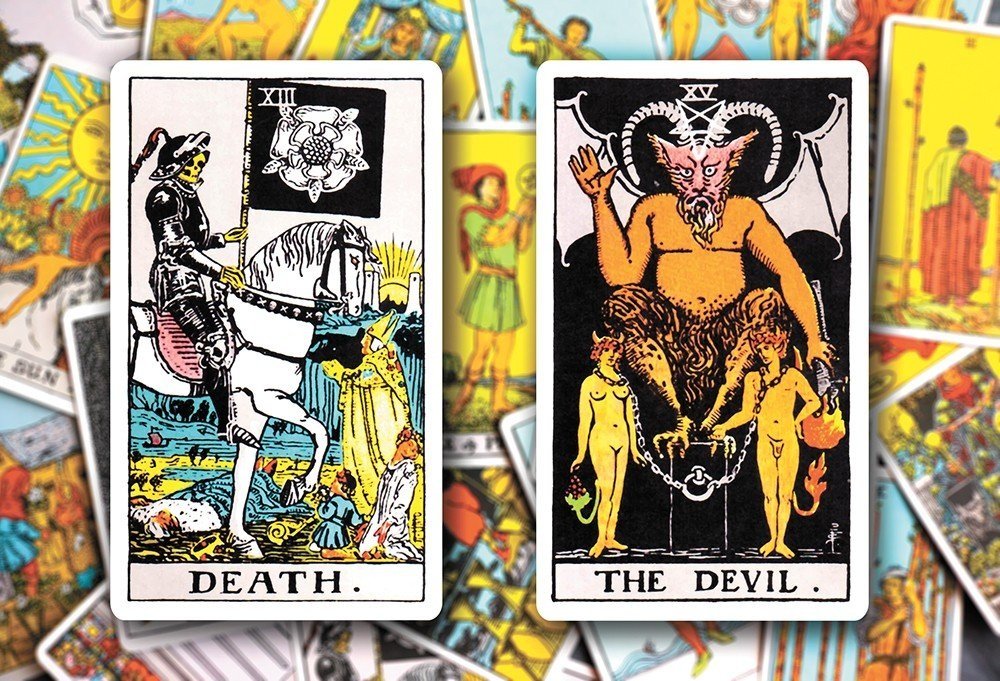

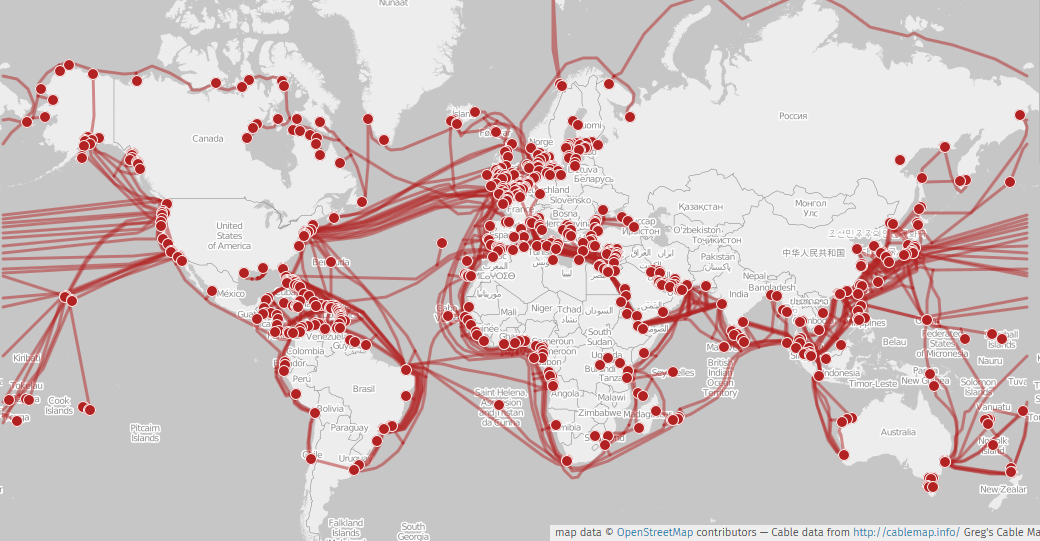

VARIETIES OF KNOWLEDGE INSTANTIATION

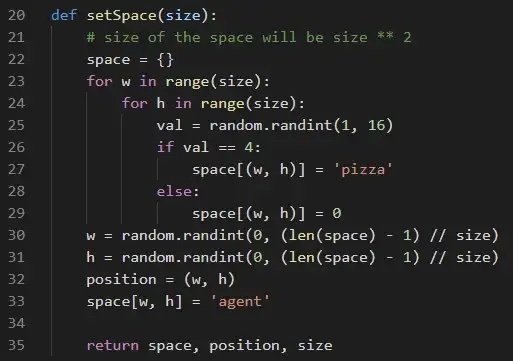

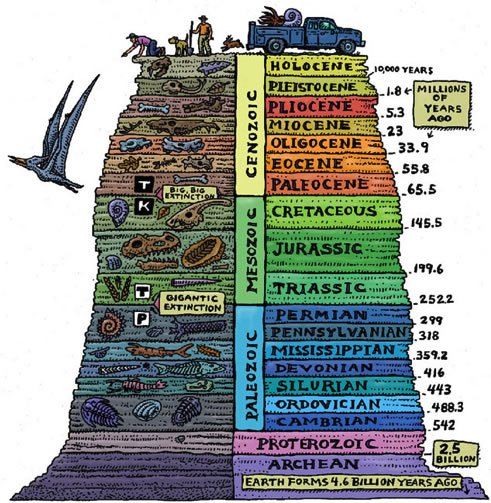

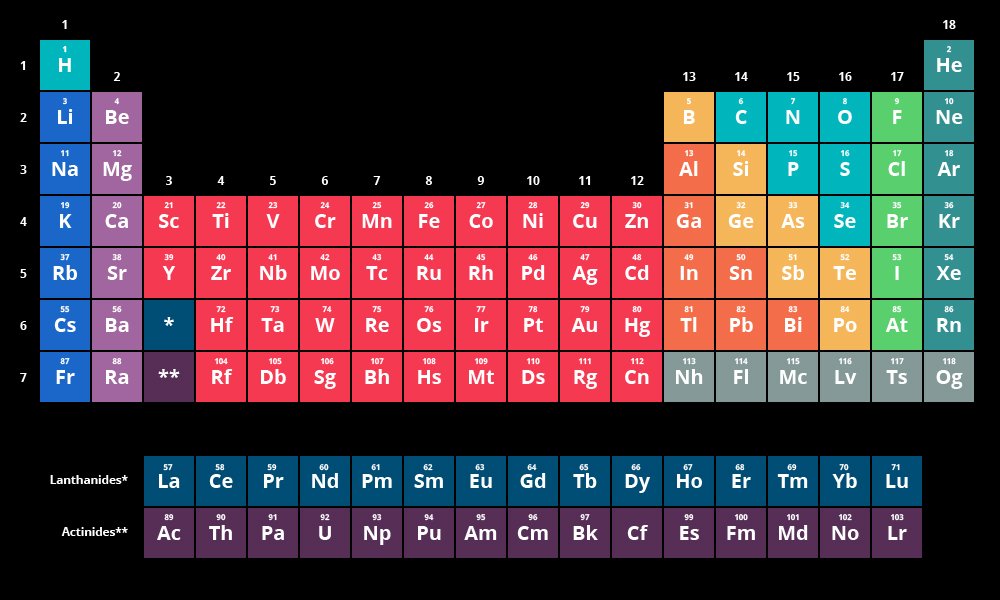

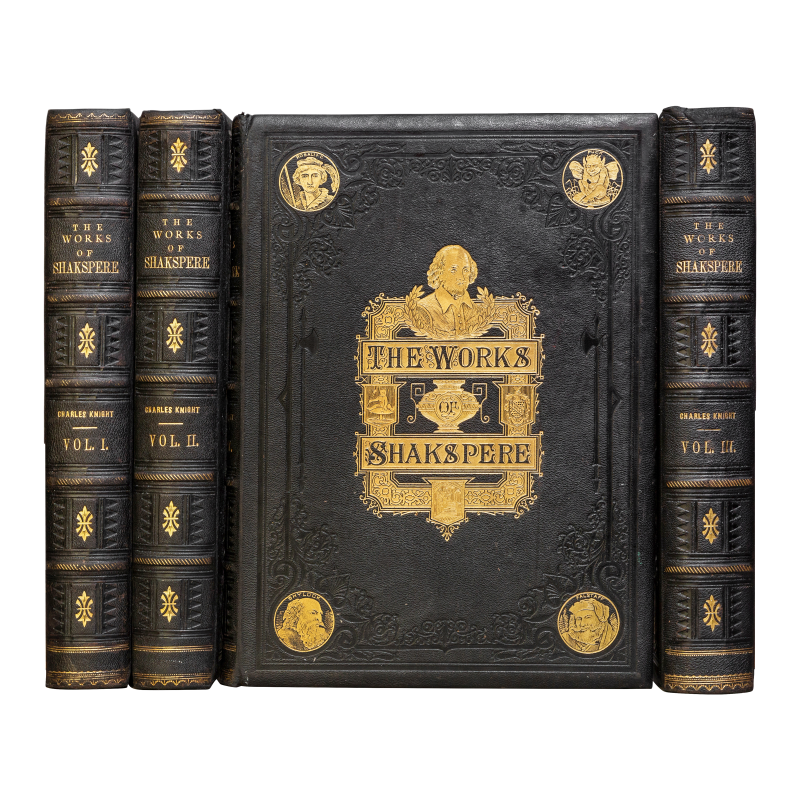

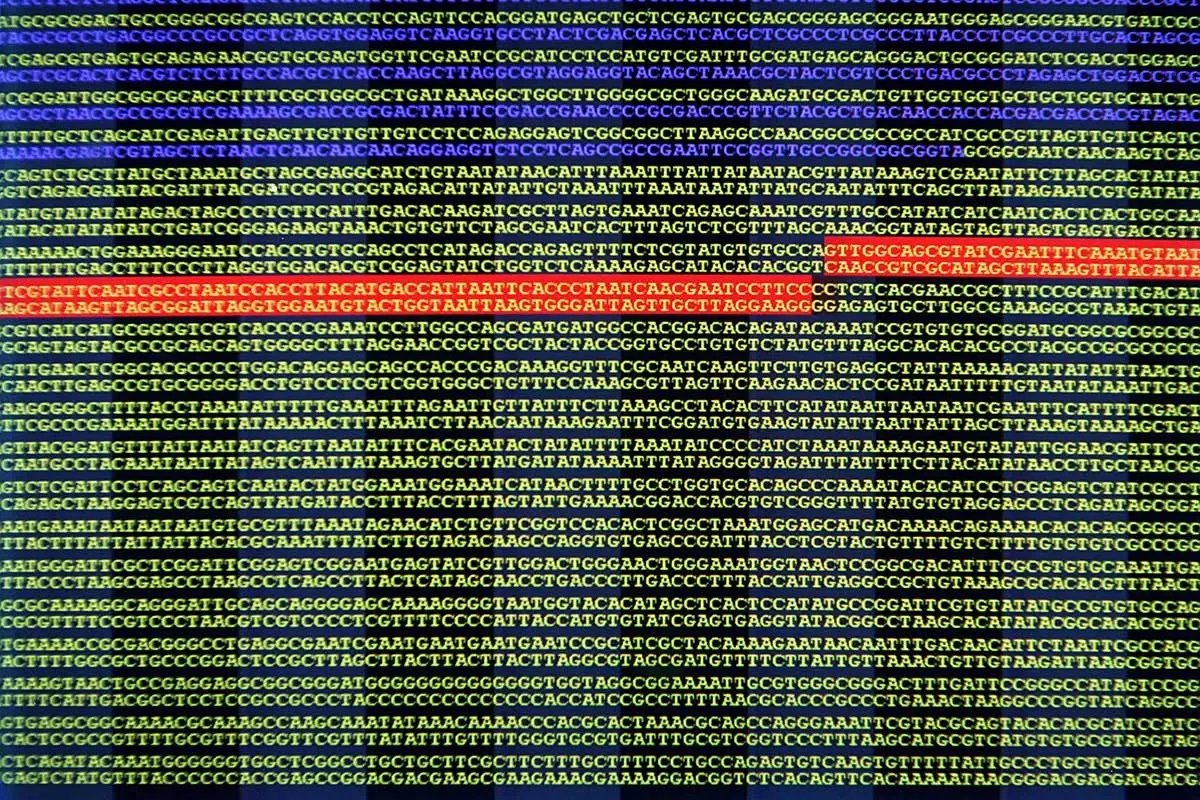

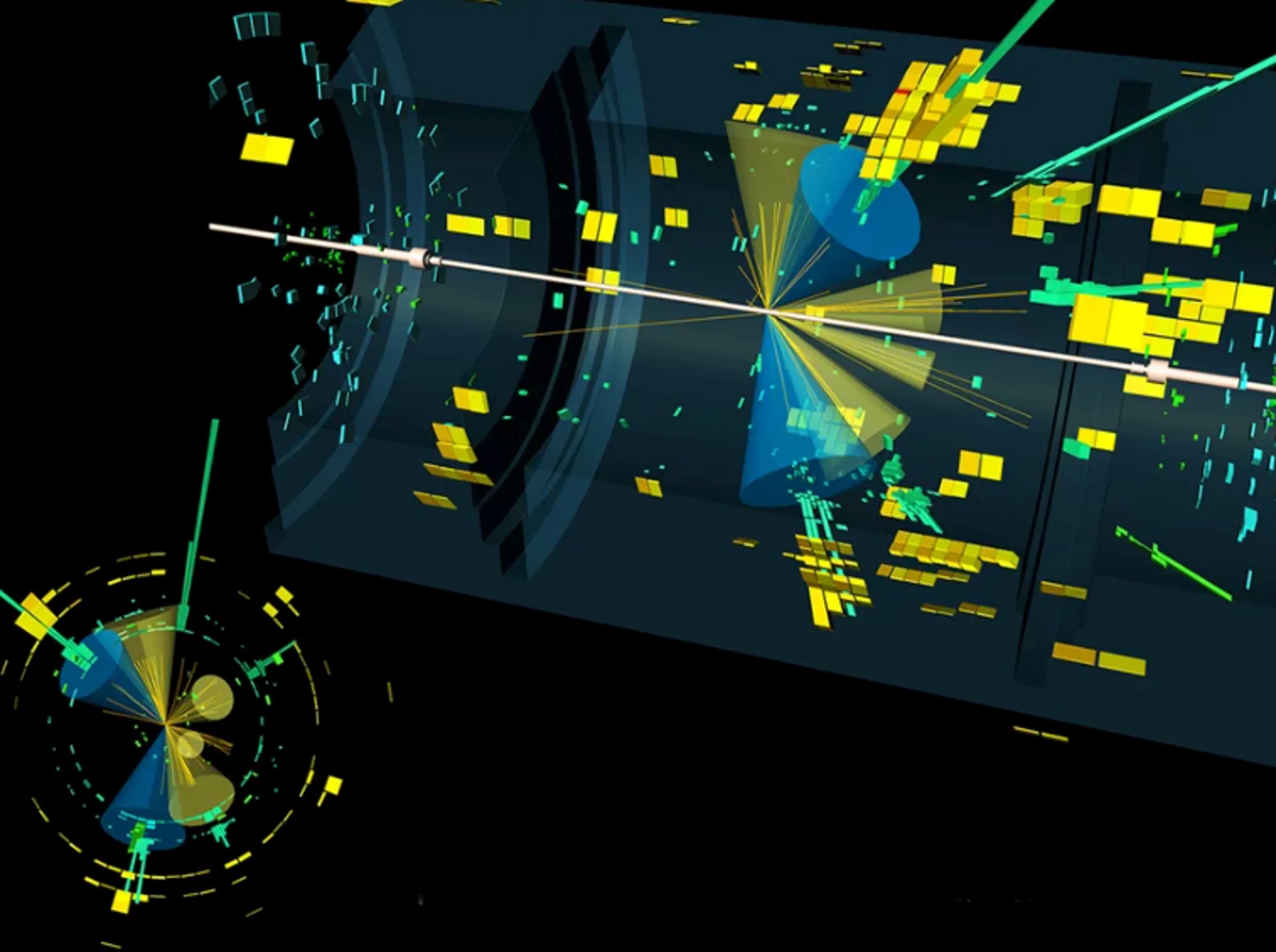

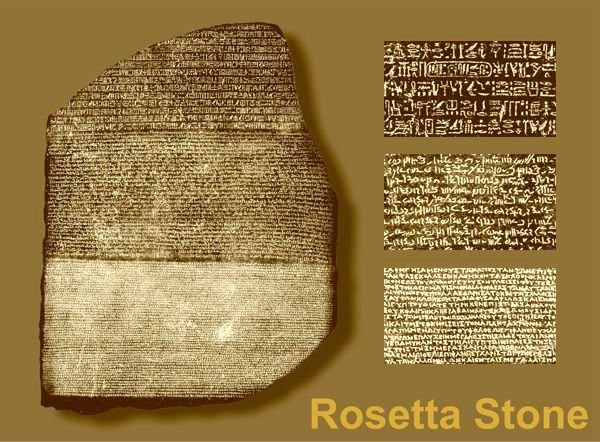

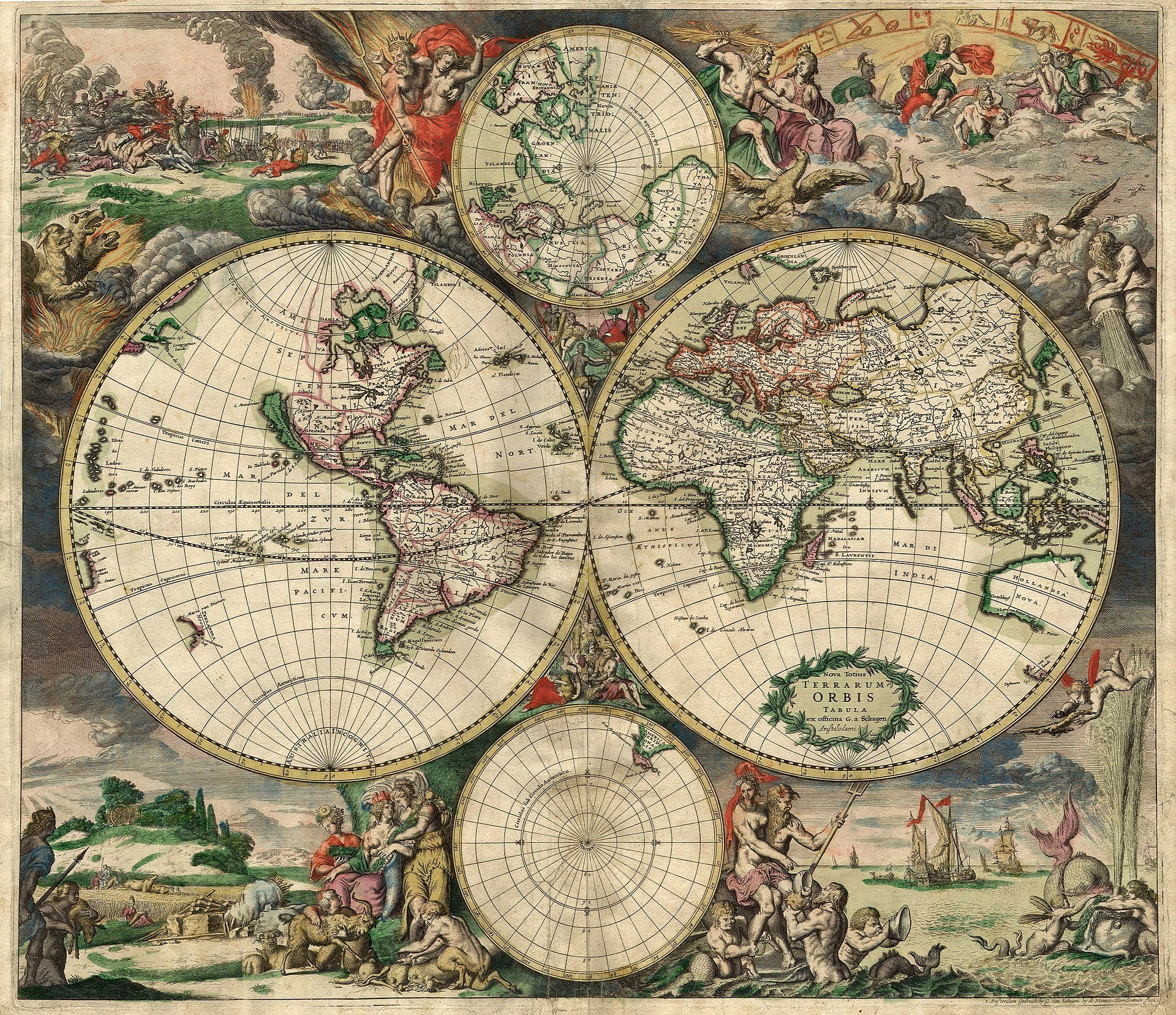

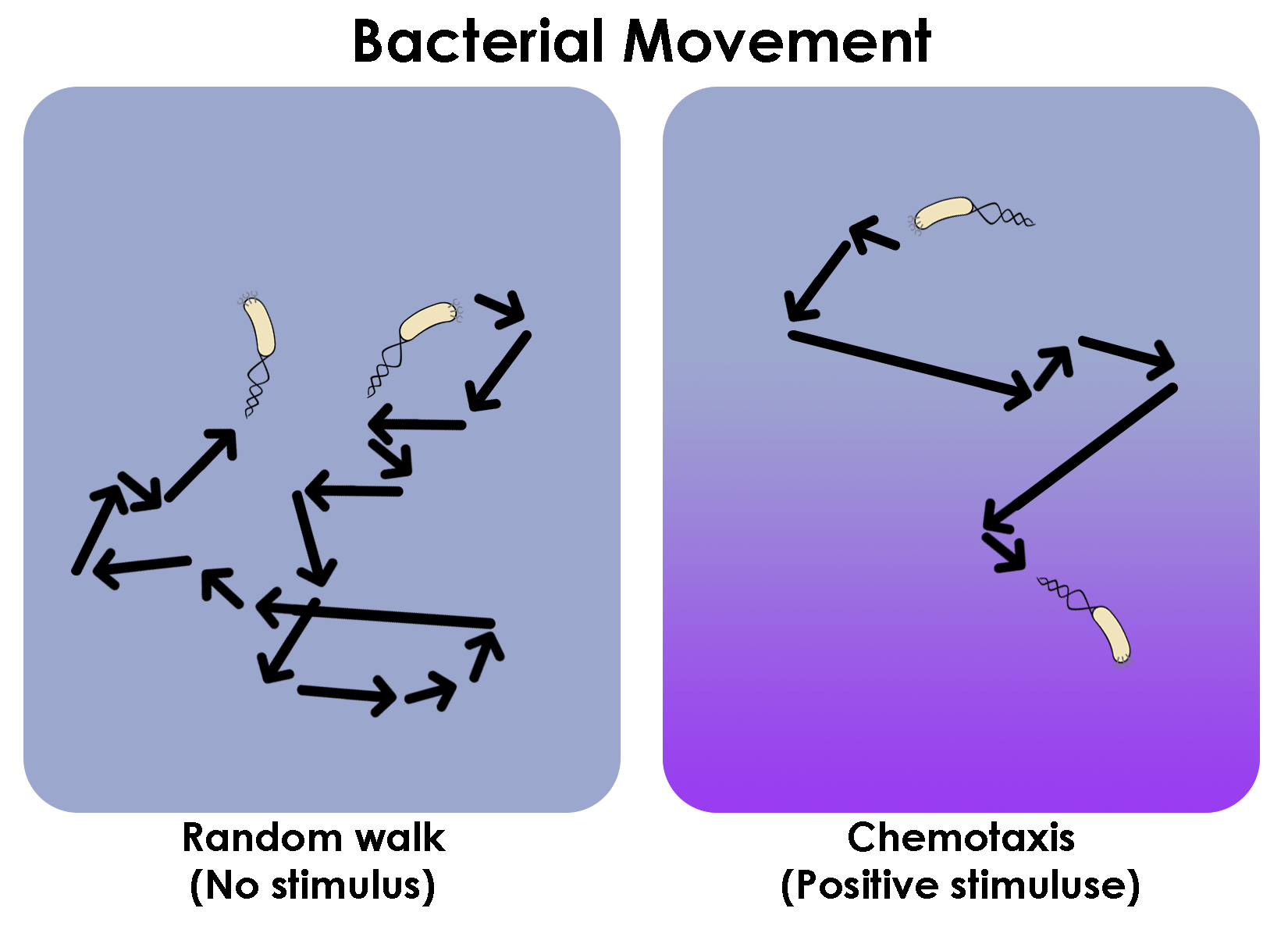

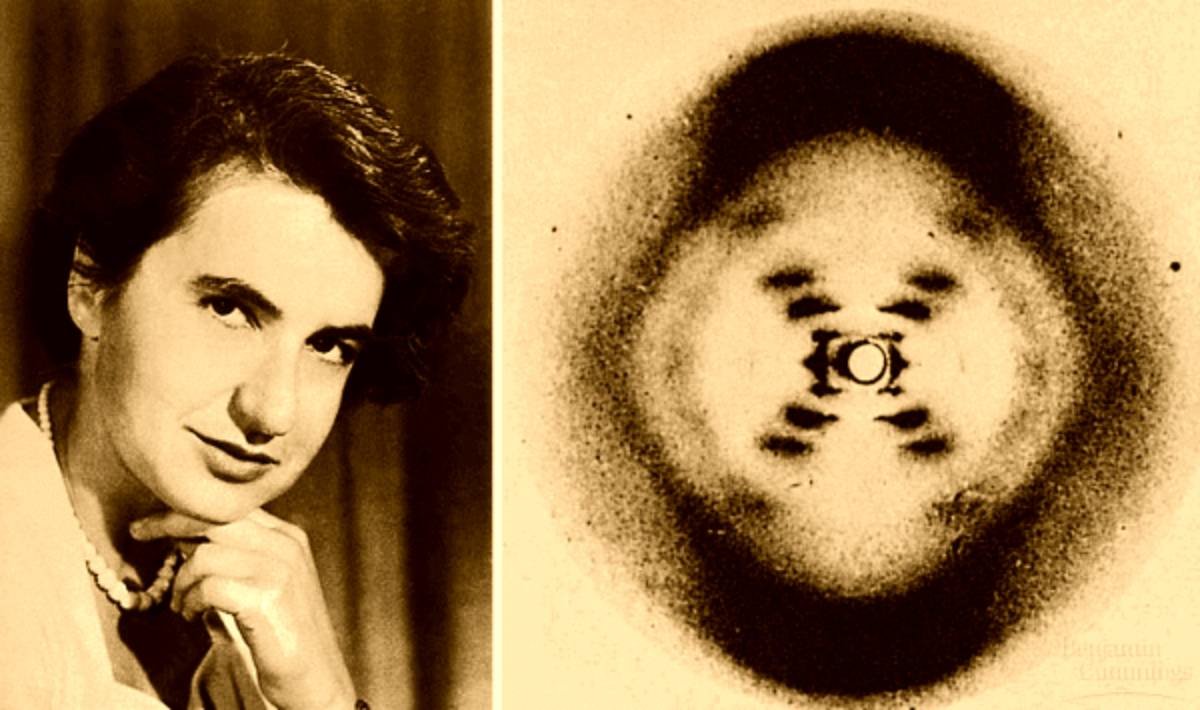

Prepare in advance enough sets of these 32 knowledge scenario cards for the class working in pairs. Here are the images in an unrestricted Google Doc.

INITIAL SLOW REVEAL

Assign student pairs randomly. Deliberately shuffle one of packs of 32 cards and, with ceremony, deal them facing down to the student pairs, one at a time. Each pair will now have several cards. At this stage students only see the images and descriptors dealt to them. Inform students that they will attempt to unpack their assigned real-life knowledge scenarios guided by the following questions:

1. What, if anything, counts as knowledge here?

2. How is knowledge physically represented or encoded here?

3. To what extent is a conscious knowing subject involved here?

4, What is the role of human culture here?

One of the students should take on the role of scribe. After five minutes of conversation time students pairs will be called upon at random to present their findings to the entire class. They should be prepared (literally) to think on their feet as they field questions from the peer audience.

A theatrical element of novelty and surprise is maintained if the classroom is darkened and each previously unseen image is projected by the teacher to the entire class. The pairs of students make their charismatic presentations in the half light!

PONDERING THE ENTire set

This time, provide each pair with a complete sets of the 32 knowledge scenario cards. Invite students to do the following—confirming that each group has completed each task before moving to the next:

1. Divide the cards into living (biological) vs. non-living physical instantiations of knowledge

2. Select all cards representing products of human culture

3. Identify cards evoking individual subjective knowledge experiences

4. Find cards that are outright rejects—that do not even count as knowledge!

Conclude by asking students to suggest—with justifications—possible additions to the set of knowledge instantiation images for future TOK students. For example, an AI-driven chatbot is conspicuous by its absence.