Optional THEME:

KNOWLEDGE AND LANGUAGE

INDUCTION AND DEDUCTION

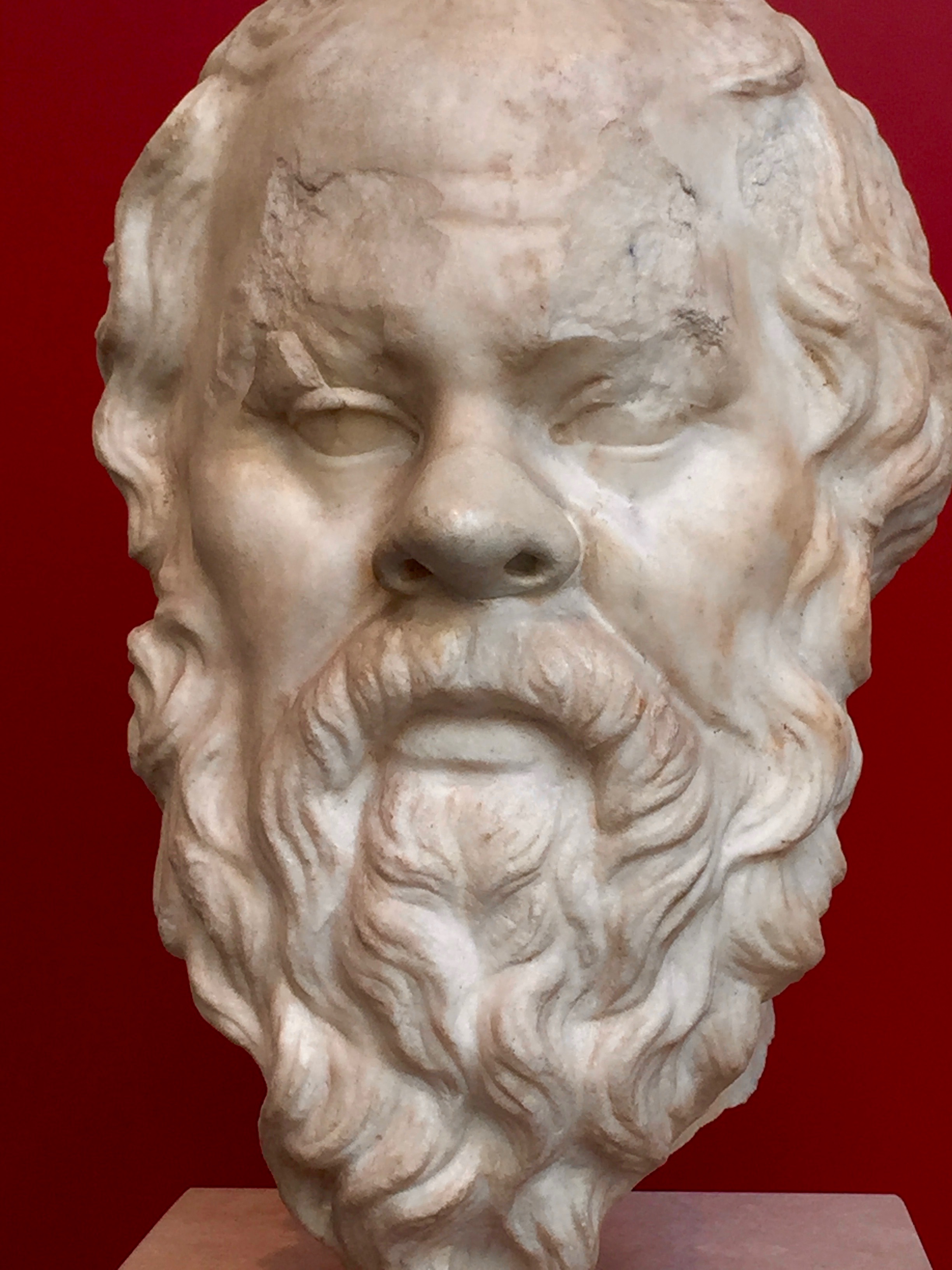

Socrates nearly always features in syllogism examples, and for good reason. He was willing to die by hemlock poisoning rather than be banished from his beloved Athens for the crime of fostering subversive critical thinking in the public arena. He claimed no original knowledge and left no writings of his own. His wisdom lives on because his life and work were championed in the works of Plato. Socrates declares (in Plato's Theaetetus: 150) that “god constrains me to serve as midwife, but has debarred me from giving birth.”

Socrates' maieutic method (mid-wife-as-opposed-to-didact) is, of course, the watchword for effective, constructivist TOK teaching!

It is essential that TOK students appreciate the difference between deduction and induction. Experience has shown that even the strongest students, who can often parrot the definitions, are initially confused when questioned using real cases. I find it worth teaching deduction and induction from scratch using an interactive lecture presentation before proceeding to the class activities

DEDUCTION: LOOKING AT SYLLOGISMS

Aristotelian logic hinges on deduction. Deduction is reasoning from the general to the particular. As in the oft repeated syllogism:

1. All men are mortal

2. Socrates is a man

3. Socrates is mortal

A deductive argument can provide logical certainty without providing useful information about the real world. For this reason sound deductions are recognized as “valid” rather than “true.” If any of the original premises are incorrect or absurd, the conclusion of the syllogism may be worthless despite its inescapable, internal logical consistency.

1. All women are mortal

2. Socrates is a woman

3. Socrates is mortal

1. All goats have six legs

2. Socrates is a goat

3. Socrates has six legs

A large ample size of white Swannery denizens

INDUCTION AND CONTINUITY

The world exhibits underlying order and continuity. Our knowledge of this seems partially a priori and partially the product of discovery by trial and error. For instance there is evidence to suggest that infants expect objects to fall down and know in advance that objects increasing in size are getting closer.

PRIMACY OF INDUCTION?

Predictability is the assumption underlying inductive reasoning, whereby we generalize from a set of particular instances. If deduction is reasoning from the general to the specific; then induction is arriving at the general from the specific. There is disjoint with this reversal. The logic is broken. Induction may be inextricable from how we encounter a more or less uniform world, but we must concede that inductive reasoning is psychological rather than strictly logical. Why?

Every time I see a swan it is white...

I conclude that all swans are white

Cygnus atratus: a large black waterbird from Australia

“Now it is far from obvious, from a logical point of view, that we are justified in inferring universal statements from singular ones, no matter how numerous; for any conclusion drawn in this way may always turn out to be false: no matter how many instances of white swans we may have observed, this does not justify the conclusion that all swans are white.”

CLASS ACTIVITY I: APPLYING INDUCTIVE

AND DEDUCTIVE REASONING TO SOME REAL DATA

Allow students to work in pairs. Provide the graph of the relationships between body mass and maximum lifespan in birds and mammals and the guiding questions. Printable pdf.

Encourage students to read closely the annotation that explains the red and blue graphs and animal silhouettes. Students with French or Spanish will almost certainly work out from etymology that volant means flying. Allow a timed 12 minutes to answer the guiding questions. Remind students that intention here is to differentiate between deduction and induction; not to learn intriguing facts about animal lifespans.

1. What is the general relationship between body mass and longevity. Did you decide this by deduction or induction?

2. Generally how does a flying vs. a non-flying lifestyle make a difference to the general relationship between body mass and longevity. Did you decide this by deduction or induction?

3. Mark boldly on your graph where you estimate the following animals would appear:

A. Grizzly bear

B. Mole

C. Etruscan pygmy shrew (weighing only 1.3 grams)

D. Pelican

E. Homo sapiens

Be precise: did you make each of your five decisions by deduction, induction or a combination of both? What were some of the interesting details that arose during your discussion.

Relationships between body mass and maximum lifespan in birds and mammals.

Silhouettes highlight a selection of species with much longer or shorter lifespans than expected given their body size. These species are (A) Myotis brandtii, Brandt's bat; (B) Heterocephalus glaber, naked mole rat; (C) Vultur gryphus, Andean condor; (D) Loxodonta Africana, African elephant; (E) Dromaius novaehollandiae, emu; (F) Dorcopsulus macleayi, Papuan forest-wallaby; (G) Ceryle rudis, pied kingfisher and (H) Myosorex varius, forest shrew.

Blue points and line represent volant birds and mammals. Red points and line represent non-volant birds and mammals. Blue triangles represent bat species and red triangles represent non-volant bird species.

Healy, K et al. (2014) Ecology and mode-of-life explain lifespan variation in birds and mammals, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0298

CLASS ACTIVITY II: FALSIFICATION

AS THE DEMARCATION OF SCIENCE

After calling on students to report back their findings on the animal lifespan activity, quickly challenge them more profoundly with the following Knowledge Question:

If science is so dependent on induction—a psychological rather than logical process—does the whole edifice of science have no solid foundation? Is this an unsurmountable problem?

Finally, show students the BBC How can I know anything at all? animation exploring Karl Popper's response to the unsettling problem of induction in the sciences. The animation is succinct, and worth showing at least twice.

Follow up with a lively whole class consolidation discussion; referring back to the induction as a shaky foundation for science Knowledge Question and emphasizing the importance of assimilating valuable new TOK vocabulary like: conjecture, refutation, falsification, demarcation and pseudoscience.

The sun will rise tomorrow...

1. How could you arrive at this conclusion by induction?

2. How could you arrive at this conclusion by deduction?

“As for Adler, I was much impressed by a personal experience. Once, in 1919, I reported to him a case which to me did not seem particularly Adlerian, but which he found no difficulty in analyzing in terms of his theory of inferiority feelings, Although he had not even seen the child. Slightly shocked, I asked him how he could be so sure. “Because of my thousandfold experience,” he replied; whereupon I could not help saying: “And with this new case, I suppose, your experience has become thousand-and-one-fold.” ”

INDUCTION AND DEDUCTION QUIZ

Here is a pdf of my non-graded diagnostic quiz. The original is a Google Form.

Highly motivated students should read this pdf of Science as Falsification by Karl Popper. This is an excerpt from Popper’s book, Conjectures and Refutations (1963).

A learned Soviet psychologist

CONVERSES WITH AN Uzbek peasant

The Russian Island of Novaya Zemlya

Source: New York Times

Conversation with famous Soviet psychologist, A. R. Luria and an Uzbek peasant in Central Asia in 1931.

“In the far North, where there is snow, all bears are white. Novaya Zemlya is in the far North, and there is always snow there. What color are the bears there?” A peasant replies: “There are different sorts of bears.”

The psychologist repeats the syllogism.

Peasant: “I don't know. I've seen black bear. I've never seen any others... each locality has its own animals: if it's white, they will be white; if it’s yellow, they will be yellow.”

Psychologist: “But what kind of bears are there in Novaya Zemlya?”

Peasant: “We always speak only of what we see; we don't talk about what we haven't seen.”

Psychologist: “But what do my words imply?” and he repeats the syllogism.

Peasant: “Well, it's like this: our Czar isn't like yours, and yours isn't like ours, your words can be answered only by someone who was there, and if a person wasn't there, he can't say anything on the basis of your words.”

Psychologist: “But on the basis of my words, ‘In the North, where there is always snow, the bears are white,’ can you gather what kind of bears there are in Novaya Zemlya?”

Peasant: “If a man was 60 or 80 and had seen a white bear and had told about it, he could be believed, but I've never seen one and hence I can't say. That's my last word. Those who saw can tell, and those who didn't see can't say anything!”

Luria, Alexander Romanovich (1979)The Making of Mind: A Personal Account of Soviet Psychology. Edited by Michael Cole and Sheila Cole. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Generative question:

What on earth is going on here?